Exploring hyper-local factors driving food insecurity, and the challenges facing foodbanks

Summary

A study funded by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) North East and North Cumbria (NENC) and led by researchers from Northumbria University has taken an in-depth look at the factors driving food insecurity at a hyperlocal level, in the North East.

The research findings have been illustrated in an impactful short film which captures the first-hand experiences of service providers trying to deliver food aid services whilst facing ever-increasing demand for their services, alongside a decline in food donations and rising running costs.

The study comes as households across the UK face increasing financial pressures including rising fuel costs, rising food costs and rising inflation.

Watch the film

(Measuring Food Insecurity to Inform Future Food Provision from Northumbria University on Vimeo.)

The report was published in the same week as figures released by the End Child Poverty Coalition showed that the North East has seen the biggest rise in child poverty in the country.

31% of children in the North East were living in poverty in 2010/11, but by 2020/21 this had risen to 38%. This equates to a jump from around three in ten to almost four in ten children now living in poverty in the region.

Food insecurity, sometimes referred to as food poverty, means a household cannot be sure they will have enough food in their household, or money to buy the food they need, to feed themselves and their family. Recent data from The Food Foundation shows that this is a significant issue – with some families selling their belongings to buy food.

Rising poverty causes difficulties in meeting food and fuel costs

Steep increases in poverty and child poverty in the North East are down to a number of factors, including the region consistently having the UK’s highest rate of unemployment and a prevalence of low paid work –with the area having the UK’s lowest weekly earnings.

Adding the current ‘cost of living crisis’ into the mix means that many households in the North East are facing the perfect storm.

As poverty figures rise, the number of households experiencing difficulties in meeting food and fuel costs increases, as does the number of people seeking support.

However, for organisations providing food aid, the rising costs of fuel and food have also increased, meaning they are also facing their own financial issues in providing their essential services.

Why is this research different?

The UK Government does measure household food insecurity in the Family Resources Survey. However, this survey does not provide local authorities with the localised information they need to plan their own local food aid planning and services.

This research aimed to gain a better and more-in depth understanding of local (ward) level differences in household food insecurity responses and risks, to help public health practitioners and food partners to better serve their communities.

A significant issue in assessing the effectiveness of local interventions to tackle household food insecurity is the lack of measurement of household food security. This is at both council and ward level, as well as having a strategic overview of all services.

Gathering first-hand experiences from local food aid services

“Our community shop applications increased from between 10 or 12 a month to 31 a month.”

“The cost of living crisis is having an impact on the donations. The (donation) bins aren’t as full as they used to be when we go and collect them.”

The research team worked closely and directly with food aid providers across communities in Redcar and Cleveland to get an in-depth understanding of what is driving the growing need for food aid – including foodbanks and community shops, as well as the increasing challenges facing them.

The researchers also worked with a Participant Involvement and Engagement group to co-produce a household food insecurity survey that was sent to residents in five Redcar and Cleveland wards.

The film produced as part of this research aims to highlight the first-hand experiences and challenges faced by service providers trying to deliver food aid services whilst facing increasing demands, a decline in food donations, and increased running costs.

The film also provides a summary of the need and challenges of measuring household food insecurity at the ward level.

Professor Greta Defeyter from Northumbria University led the study. She said:

“Making this film was a real eye opener. Research projects often focus on the service user rather than the experiences of the service provider. However, in terms of local food aid services the two are inextricably linked.

“Food aid services, whether food banks, community shops, or pantries are a lifeline for many households. These organisations are very knowledgeable about local need, yet as identified by all providers, including the council, there is a need to adopt a strategic approach to ensure that no household misses out.

“Everyone realises that food aid services don’t address the underlying cause of poverty but for many families they are the difference between eating or not.”

Key findings

It is important to measure at a local level

The research found considerable variation in household food insecurity across the five wards measured in Redcar and Cleveland, supporting the idea that it is important to measure household food insecurity at ward level – because each area has its own unique needs and resources.

Measuring at a local level would enable local authorities to strategically target areas of need and evaluate the impact of food related interventions on household food insecurity more effectively.

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) can’t always accurately predict food insecurity

An unexpected finding was while the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) is one of the most important predictors of food security at an overall level, it cannot predict food insecurity equally across the range of ‘low or very low’ food security. This research suggests that the reliance on the IMD could potentially lead to incorrect conclusions about the geographic distribution of food insecurity within local authorities.

Local food security varies by levels of knowledge of food aid and its availability

The distribution of local food insecurity also appears to be shaped by both knowledge of and levels of food resources. The distribution of knowledge and resources, perhaps, may explain why the IMD fails to adequately predict food insecurity across the spectrum of food insecurity scores in the wards we examined.

Recommendations

At a local level there is a pressing need to understand the scale of food insecurity. There is also a need to understand who is at high risk, and what interventions work for whom, why and where? These may be cash based or food-based interventions. Local measurement of household food insecurity will help local authorities in answering these questions.

Further work – the FILL Consortium

Colleagues from Northumbria University, the University of Liverpool and the University of Sheffield have since come together to form the FILL (Food Insecurity Monitoring at the Local Level) Consortium. In September 2022 the FILL Consortium produced a new policy brief – ‘Time to meaure and monitor local food insecurity: The case for a harmonised approach across local authority areas’. The brief will be shared as part of an event hosted by the Local Government Association in October 2022. You can download the brief below.

Next steps

The research team are currently exploring piloting this survey in five local authorities, with colleagues from the University of Sheffield, the University of Liverpool and the Independent Food Aid Network.

For more information please contact: [email protected]

The project was led by Northumbria University, working with partners from Newcastle University, Teesside University and Redcar and Cleveland Council.

The work was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) North East and North Cumbria (NENC).

Thanks

With thanks to the following groups in Redcar and Cleveland who gave their time to support this project:

Guisborough Methodist Foodbank

Footprints in the Community Café

Grangetown Primary School

Next Steps Shop

Grangetown United Community Hub

Future Regeneration of Grangetown

East Cleveland Good Neighbours

We would also like to thank the Independent Food Aid Network for their contribution to the making of the film.

Related information

The links below provide further context and information around poverty, child poverty and food insecurity in the North East and nationally

Breadline Voices: Some parents have sold their belongings to buy food | Food Foundation

Three out of ten children in key worker households in the North East region live in poverty – TUC

Poverty 2022: The essential guide to understanding poverty in the UK -Joseph Rowntree Foundation

Research carried out by Loughborough University for the End Child Poverty Coalition – July 2022

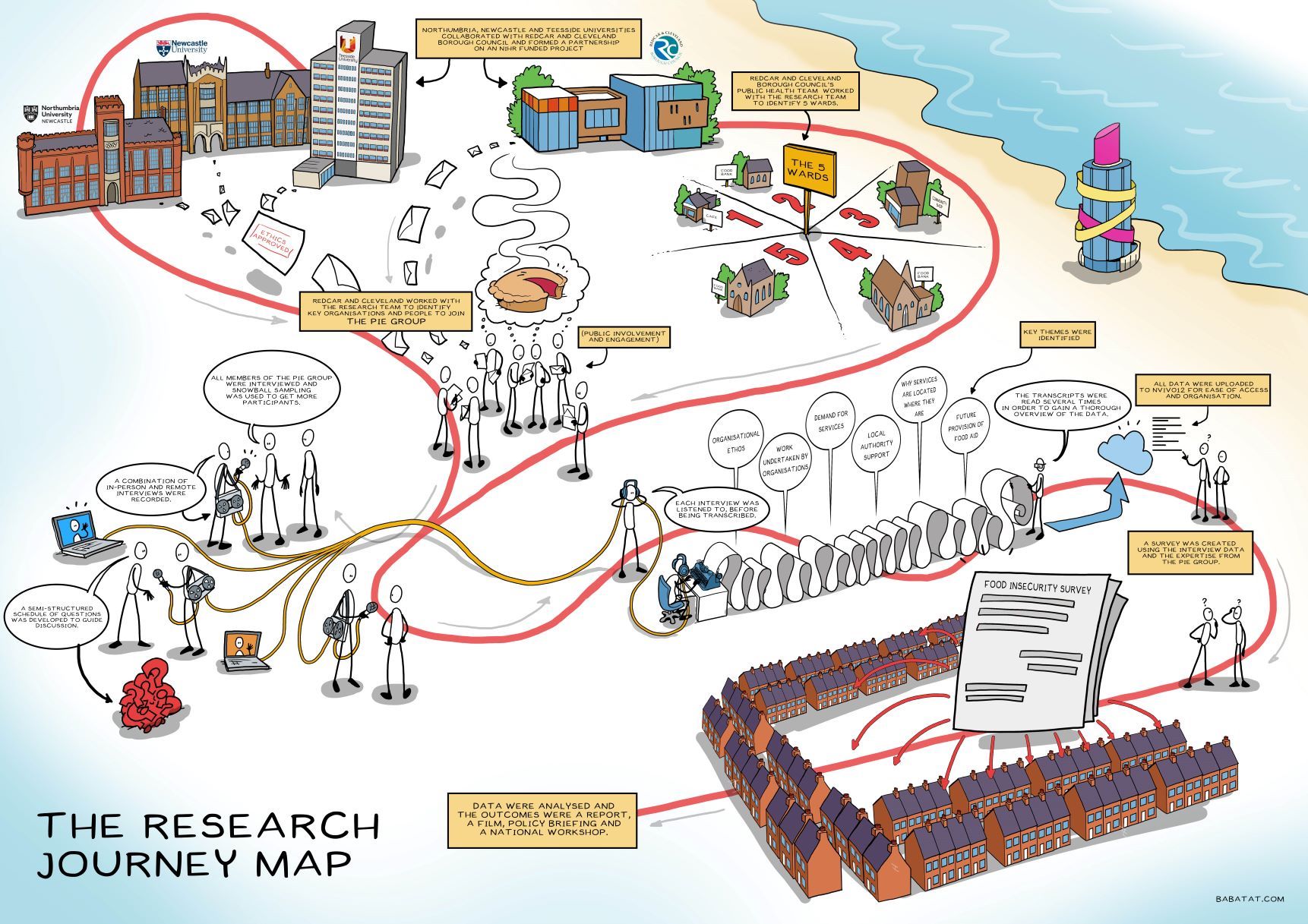

Research Journey Map

As part of this work, the team have produced a Reseach Journey Map (shown below) to provide a visual representation of the process they undertook to conduct the research. You can download a copy of the Research Journey Map below.